At the behest of Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, I recently had the opportunity to visit Ichikikushikino City in Kagoshima for a day-long shochu experience for members of the press and industry folk. Our group hit four distilleries, learned a ton, and had plenty of food and drink.

Ichikikushikino City

While the name is a bit of a mouthful even for native speakers, Ichikikushikino is a reasonably new city by Japanese standards—it was created in 2005 as a merger of the towns of Ichiki and Kushikino. Whether driving, taking a bus, or by train, you’re about 30 minutes outside downtown Kagoshima.

Ichikikushino is shochu town. Shochu is part of the lifeblood of the city of roughly 26,000 people. And, I shit you not here, it became the first place in Japan to have a “Kanpai Ordinance” for shochu in 2013, legally mandating the city and local businesses to promote honkaku shochu. I’ll kanpai to that!

If you’re into history, this is a fascinating place. In 1587, as part of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Kyushu campaign towards the end of the Sengoku period, he and his half-brother steamrolled the Satsuma Domain’s Shimazu clan. But it looks like there was no bad blood between the two clans. It’s in this area Shimazu clan daimyo Shimazu Yoshihiro staged his offense for Hideyoshi’s Imjin War to try and conquer the Korean peninsula (and eventually China) for Hideyoshi.

Only a month after their eventual retreat from Korea in November 1598, Yoshihiro brought some 70 artisans to Satsuma and some set up shop right here in Ichikikushino. The town is the birthplace of Satsuma ware. Despite the Toyotomi clan’s defeat at the Battle of Sekigahara (i.e., the birth of Tokugawa Shogunate) two years later, Yoshihiro seems to have managed his way through the tumult. He retired to Sakurajima and passed at 84 years old.

These days, besides shochu, Ichikikushino is also known for tuna—a lot of tuna. At its peak, the city had some 81 ships registered, bringing in around 18,000 tons of tuna worth around 25.5 billion yen. Tuna ramen might be famous, but I’ll take a kaisendon myself.

Hamada Syuzou Denbeegura

As Japan’s fourth-largest shochu maker per 2023 data from Teikoku Databank, Hamada Syuzou should already be a familiar name to any fan of the category. Both within and outside Japan, the company is probably best known for its lychee-fresh Daiyame and its export-only counterpart, Daiyame 40.

Hamada’s Denbeegura is where it all started. The distillery’s namesake, Denbee Hamada, began moonlighting here as a shochu distiller in 1868 while running an aroma shop and used clothing store. While more modern and industrial Denzouingura is responsible for the production of Daiyame today, the Denbeegura is about keeping the traditions from Denbee’s time alive and well.

And we’re talking about the whole shebang here. Following tradition means using the same infrastructure, like earthenware fermentation pots, maturation pots, and wooden pot stills. It also means using tools like the wooden pole to churn your fermentation so it doesn’t get too hot. The tray size you use to grow your koji on your rice. Sand under your maturation pots for earthquake protection and less heat transfer. It’s all an effort to replicate those old-school flavors.

I say “replicate,” but the truth is that Hamada Syuzou is simply still doing it this way here. During the war, Hamada Syuzou was designated an official supplier of the Imperial Japanese Navy (like Suntory and Nikka for whisky). While this deprived the locals of shochu when needed most, it did enable Hamada Syuzou to remain operational the entire time.

As the US Navy encroached upon the Japanese mainland towards the end of WW2, maybe in a precursor to Operation Olympic, the town was flattened on August 9, 1945. Twenty-five locals died, but the distillery seems to have been spared from the fires as it was on high ground. Some feared that the distillery’s chimney would make it a target for bombing, and efforts were made to hide the smoke it emitted, but they were not necessary. V-J Day was only six days later, on August 15. With Japan losing the war, the 3rd generation Denbee did what he could to help lift spirits by giving away the distillery’s stock of spirits the morning of August 17.

The museum’s pot still, from the late 1930s, is the first thing you see when you start your distillery tour. Anything made of iron was in high demand during the war, but this particular still was spared thanks to the efforts of people from Hamada Syuzou and locals. And because it was encased in brick!

Hamada Syuzou Satsuma Kinzangura

Now, here’s a wild one. Can you name a distillery inside of a former mine? I don’t mean aging in a former mine; I’m talking about distilling inside a mine. I don’t remember “pot still” being in my kid’s Minecraft inventory.

Hamada Syuzou’s Satsuma Kinzangura is precisely that. The story goes that the Satsuma Domain was short on money and didn’t have a lot of local resources to fill the coffers. With the rise of mining, rather than simply panning, for gold at the end of the 15th century, the race was on to find gold across the country. Satsuma Domain found theirs in a few different mountains, and by 1660, the Kinzan Gold Mine already had about 7,000 people digging there. Mitsui took over operations in 1909, and the mine was Japan’s first to have facilities for gold cyanidation.

That technique paid off because this mine produced the most gold in Japan every year from 1919 to 1923. The digging went as far as 347m below sea level, and the mine has a total length of 120km. However, as the decades passed, it became less and less profitable. Eventually, the site was turned into a “gold mine theme park” that operated from 1988 to 2003. In 2005, Hamada Syuzou took over the site, and it’s now the Satsuma Kinzangura (“Satsuma Gold Mountain Distillery”).

If you know anything about a distillery’s operation, you’re probably asking yourself how they put one inside a mountain. It’s one thing to throw some barrels in a train tunnel or former coal mine for a few years, but this is a different beast: sending in tons of raw ingredients and coming out with bottles of shochu.

Since modern mining involves moving tons of rock out of the mine, using the same rail to move tons of stuff into the mine is apparently not too much of a stretch. The tram used by the gold mine theme park to transport visitors into the mine is the same one used by Hamada Syuzou to haul tons of potatoes and other ingredients for their distillation.

Safety was the next question that came to my mind. We’re talking about creating a highly flammable liquid (ethanol) in a place where you definitely don’t want a fire. Hamada Syuzou says they got the all-clear here as the original ventilation systems were deemed suitable. This deep in a mine, the temperature and humidity remain largely the same year-round.

Making yellow koji, fermentation, distillation, and maturation happens within the mine. These days, bottling is the only operation component that occurs above ground. Once bottled, most of these head to the market as the 3-year matured “Kinzangura” shochu. Some bottles head back down into the mine, though — Kinzangura offers a program where visitors can purchase a bottle and keep it in the mine for their desired duration. While this isn’t a cask ownership program where you can check the progress of maturation along the way, it’s an interesting way to attract repeat visitors.

Most sweet potato honkaku shochu is made via a two-step fermentation process. First, let your koji multiply in water (step one), then add your potatoes and continue the fermentation (step two). This method was developed in the early 20th century because it reduces the risk of ruining your batch.

Meanwhile, Satsuma Kinzangura uses an older method called “Donburi Fermentation.” It’s more simplistic—throw all your water, ingredients, and koji in a pot and let it ferment. The method dates back to the Edo period, or 1603 to 1868. Sweet potatoes were introduced to Kagoshima in 1705. Ninety years later, in 1795, we have the first written record of using them to partially replace rice when making shochu.

The Tokugawa shogunate introduced something akin to a license for brew sake–dubbed a “sakekabu,” aimed at assuring enough rice left to eat–in 1657. That said, homemakers, mothers, and daughters nationwide could still make koji for their miso and soy sauce. What’s more, home distilling of shochu wasn’t made illegal until 1895. So, in Kyushu, if you were already fermenting at home, brewing up your moromi to throw on the village pot still seems like an obvious extension.

And the pot still? It’s a wooden kabuto-style still, which we’ve covered before. Distillate condenses on the underside of a vessel to trickle down to a collector within the body of a still. No lyne arms or worm tubs are required.

In keeping with the tradition of women being in charge of the family shochu, the Satsuma Kinzangura employs only women to run the fermentation/distillation today.

I’ve been to plenty of distilleries worldwide, but the Satsuma Kinzangura is an interesting case study of running an underground distillery. Oh, and speaking of Minecraft, you can grow potatoes in caves!

Yamatozakura Shuzo

Earlier, I said Ichikikushikino is a shochu town, and here’s a great example of why: Yamatozakura is Kagoshima’s smallest distillery, and it’s right across the street from the mighty Hamada Syuzou.

Yamatozakura is, for all intents and purposes, a one-person show. Wakamatsu-san is the fifth-generation owner and master toji who does essentially any technical task himself. Waking up in the wee hours to check on koji, processing Kogane Sengan sweet potatoes, monitoring fermentation, and distilling — it’s all him.

What does that mean for numbers? A standard season here yields 250 koku, or roughly 45,000L of shochu. That’s a mere 25,000 1.8L bottles per year. Whisky fans may say, “Oh well, that’s not too small,” but we’re talking about shochu. For reference, the aforementioned Hamada Syuzou churned out 119 million liters of the honkaku shochu in the year ending June 2024.

In addition to the lack of permanent staff under him, Wakamatsu-san’s distillery has zero mechanization. He’ll spend three hours preparing his 175kg of potatoes—no drums, conveyor belts, or fancy machinery. Any shochu coming out of the distillery is handmade.

Instead, the focus here is on respecting the knowledge gained by generations that came before him. He provided an example with his koji boxes: they’re the perfect shape, size, and depth, with zero spillage whatsoever. Someone before him found this the ideal size, so he’s using it as-is. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Yamatozakura’s main bottle uses Kogane Sengan sweet potato, known for its high starch content and easy to tell by its beige skin. Another release uses Beni Satsuma sweet potato, which may be more easily recognizable as a sweet potato because of its purple skin. I mean, it’s part of Unicode now: 🍠

Shiraishi Shuzo

Just down a nearby street is Shiraishi Shuzo. The modus operandi here is “farm to table.”

Plenty of Japanese food and beverage focuses on ingredients, and Shiraishi Shuzo has taken this to the extreme by growing its own potatoes 100% naturally. Not just some portion, either: every shochu coming out of this distillery uses only potatoes grown on one of ten nearby fields. They use no herbicides, chemical or organic fertilizers, pesticides, or any other agricultural chemicals.

This approach significantly impacts yield: Shiraishi-san estimates he only gets about half the volume of potatoes versus a standard modern field.

Modern? If anything, Shiraishi Shuzo is trying to go back in time. He’s working towards reviving Meiji period techniques and flavors in his shochu. The distillery was founded in 1894, the 27th year of the Meiji era, so he’s essentially trying to go back to the very roots of the distillery via the roots of his potatoes.

Shiraishi-san also says that farmers and shochu makers want different things from their potatoes. While farmers may be concerned with yield per hectare, Shiraishi-san is trying to find what works best for them. Part of that is highlighting the hyper-locality offered in Ichikikushikino.

In an effort to revert to the Meiji period recipes, Shiraishi Shuzo is looking to reduce their use of rice. Shiraishi-san says that this year, the ratio of rice to potato is 1:6. Next year, he’ll aim for 1:7. That comes at a price: fermentation time here is anywhere from 30 to 60 days!

Shochu Cocktails & Local Eats

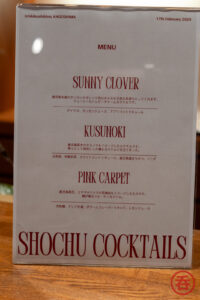

Our day was end-capped with a tasting session featuring distillers/staff and bottles from all four distilleries, a trio of shochu cocktails highlighting the bottles, and a lineup of Ichikikushino’s local cuisine.

I’ll let the photo captions do the explaining here.

Thanks to the Agency for Cultural Affairs for organizing the trip!

Hi there! I created and run nomunication.jp. I’ve lived in Tokyo since 2008, and I am a certified Shochu Kikisake-shi/Shochu Sommelier (焼酎唎酒師), Cocktail Professor (カクテル検定1級), and I hold Whisky Kentei Levels 3 and JW (ウイスキー検定3級・JW級). I also sit on the Executive Committees for the Tokyo Whisky & Spirits Competition and Japanese Whisky Day. Click here for more details about me and this site. Kampai!