While probably old news to many, in December 2024, much of the sake industry celebrated the addition of “Traditional knowledge and skills of sake-making with koji mold in Japan” being listed as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. What are the implications for the category, if any?

UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list started back in 2008 to celebrate diversity in cultural heritage and raise awareness about its importance. In reality it’s actually three lists:

- Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (the main list)

- List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding

- Register of Good Safeguarding Practices

Despite how you may hear about sake breweries with no heirs willing to take over the family business, the collective sake industry and Japanese government have decent support mechanisms in place: unions, record-keeping, seminars, hands-on training, technical advice, and more. The National Tax Agency earmarked some 1.59 billion yen to support sake & shochu in FY2024, and they are budgeting 2.15 billion yen for FY2025. Sake-making with koji mold doesn’t necessarily need urgent safeguarding from the worldwide community — Japan has it under control. So this new entry falls under the main list.

For Japanese sake, getting to UNESCO was a two-step process. First, sake-making had to be recognized as an Intangible Cultural Heritage (登録無形文化財) within Japan — this happened back in 2021. In 2023, Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs then applied to UNESCO, and acceptance was announced back in December of last year.

At the heart of that effort was an organization created back in 2021 called the “Japanese Traditional Sake Brewing Technique Preservation Association.” At the helm is Shinuemon Konishi, president of Konishi Brewery. The company goes back to 1550 and their flagship Shirayuki brand claims to be the oldest brand of sake in Japan, first released in 1635. Konishi Brewery already knows something about preserving traditional sake brewing techniques.

One thing that struck me as slightly odd about this UNESCO registration is the deliberate use of the word sake rather than nihonshu. As tippsysake explains, the Japanese government has already gone out of their way to acquire GI for “nihonshu,” designating sake made in Japan entirely from Japanese ingredients. I guess this UNESCO listing was more about recognizing the techniques and traditions involved than the ingredients’ origins. As such, they went with the slightly more broad term: sake.

Somehow, shochu and awamori—both of which also use koji mold and multiple parallel fermentation—seem to have taken a back seat in the actual nomination form and on UNESCO’s official webpage for the listing. If we’re talking about Japan’s traditions with koji techniques, I wish they’d also call more attention to the distilled side. Shochu’s history goes back some 500 years, so as far as I’m concerned, it is just as important an intangible cultural heritage of Japan.

JSS: Journey & Sake

The Japan Sake & Shochu Makers Association (JSS) held a media event at their Shimbashi sampling/seminar space (the Japan Sake and Shochu Information Center) just before the official announcement of the UNESCO listing last year. Topics covered include the UNESCO listing and the origins of the regionality of sake.

Will sake repeat the success of Washoku overseas thanks to UNESCO?

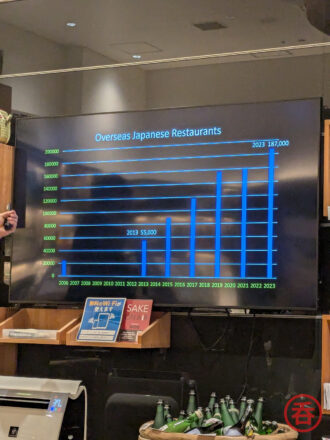

Imada-san, who runs the Center, made the case that in tandem with the UNESCO inscription of Washoku as an Intangible Cultural Heritage back in 2013, the number of Japanese restaurants outside of Japan ballooned from 55,000 that year to triple to 187,000 ten years later in 2023.

Will the same happen for sake? I don’t exactly agree with this take. Rather than a UNESCO listing as an Intangible Cultural Heritage–how many people even know what that is?–I would instead attribute the popularity of Japanese cuisine outside of Japan to a host of other factors.

Over this same period, the rise of social media shifted Japan from appearing exotic and closed to an actual country you can (and probably should) visit. In only a handful of years, Japan became a bucket list item or a honeymoon destination. Tourists are flooding the streets of Kyoto, and Tokyo has become the world’s #1 city for all sorts of metrics. In 2013, Japan welcomed just over 10 million tourists from overseas. By 2022, that number (also) tripled to around 32 million visitors.

It stopped being nerdy to like anime… depending on the anime. Ramen became something you regularly eat on a night out, izakaya emerged as an alternative to pricey omakase sushi, and edamame found its way onto menus of places entirely unrelated to Japan. Miso! Natto! Pass me the green tea! I’ll take a highball instead, though.

People also started to compare daily life in their own countries to their image of life in Japan, even if the details were somewhat sensationalized. “In Japan, elementary students walk to school alone.” “Japanese train conductors formally apologize when their trains are 20 seconds late.” “Even during the worst natural disasters, Japanese people patiently wait in line to receive their rations of food and water.” “In high trust societies like Japan, the public good takes priority over personal freedoms.” We’ll probably hear how Japan is living in 2050 until around 2035. Someone will probably still be trying to make a joke about fax machines then, too.

I won’t go on, but I just wanted to make the point that while I’m sure the UNESCO addition of Washoku didn’t hurt, I suspect it had little to do with the number of Japanese restaurants outside the country. Instead, I think Japan became a more significant part of many people’s lives, and the demand for Japanese restaurants simply increased.

Sake regionality

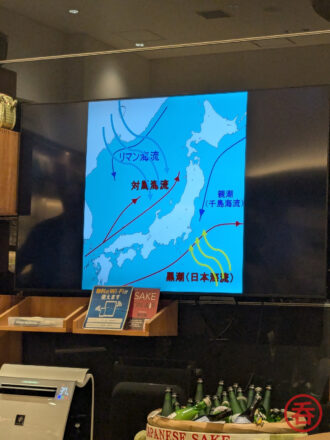

Getting back to sake, the next part of Imada-san’s presentation focused on how ocean currents and geography have impacted Japan’s climate and, thus, the regional preferences of preferred food and drink.

The basic idea is that the warm Kuroshio Current, originating near the Philippines, runs from the Pacific coast of Kyushu up to the Boso Peninsula (near Chiba Prefecture). There it’s met by the colder Oyashio Current, originating in the Arctic Ocean. This means that on the Pacific side of Japan, currents are warmer towards Kyushu, and colder up in Hokkaido and Tohoku.

On the Sea of Japan side of the country, there’s something similar going on. The warmer Tsushima Current passes by Kyushu and the Chugoku region of Honshu, then towards Niigata and the prefectures of Tohoku it meets the Liman/North Korean Cold Current. One difference from the Pacific side is that on the Sea of Japan side, the intersection of currents is met with winds from the Siberian High. During the winter, the warm water from the south hits those cold winds, giving us Japan’s glorious Snow Country. When things warm up, it’s no surprise this is one of Japan’s best places to grow rice.

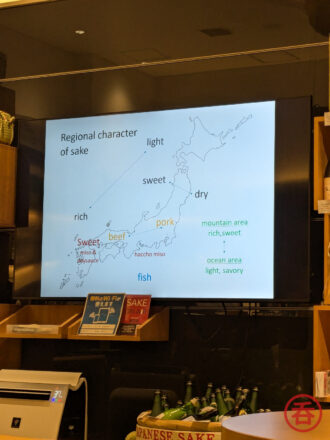

This has understandably led to significant regional differences in the flavor profiles. Overall, food in the Kyushu and southern regions of the country trends towards sweeter: think sweet miso, thicker/sweeter soy sauce, yuzu. And… sugar! Back in the days of isolationism under the Tokugawa Shogunate, Dejima was essentially Japan’s only contact with the Western world, and the Portuguese (and later Dutch) traders brought sugar with them.

To match those foods, sake in the southern regions trends towards being richer and sweeter in flavor.

On the other end of the country, the food focus was largely on taking advantage of rice and other grains. If you could get it, something from the ocean. If you can’t do either, there’s the always-classic potato.

As such, many sakes from the northern coasts tends to be light and savory. Niigata’s sake, for example, is relatively well known for being “tanrei,” or light and crisp.

In closing, I just want to note that koji did not originate in Japan. Making alcohol from koji isn’t originally from Japan either. What is from Japan is the techniques and culture that survived the roughly two millennia since its introduction to the country. Today, sake is inseparable from nearly any Japanese custom involving anything worth celebrating, mourning, or hoping for. Wedding? Sake. Hanami? Sake. New Year? Sake. Matsuri? Sake. Does your company want to hit their sales numbers? Sake. Praying to your local god for rain to make this year’s rice harvest good for… more sake? Sake. Want to catch a lot of fish this year? Sake. Funeral? Sake.

Maybe in a few years we’ll see “Sake drinking culture in Japan” added to the UNESCO list as well.

Hi there! I created and run nomunication.jp. I’ve lived in Tokyo since 2008, and I am a certified Shochu Kikisake-shi/Shochu Sommelier (焼酎唎酒師), Cocktail Professor (カクテル検定1級), and I hold Whisky Kentei Levels 3 and JW (ウイスキー検定3級・JW級). I also sit on the Executive Committees for the Tokyo Whisky & Spirits Competition and Japanese Whisky Day. Click here for more details about me and this site. Kampai!