In April 2021, the Japan Spirits & Liqueurs Makers Association (JSLMA) implemented industry standards for Japanese whisky. The hope was that it would provide an impetus for association members to be more forthcoming about the origins of products they label as Japanese whisky.

- Red Flag #1: It’s not clear which company and/or distillery makes it

- Red Flag #2: It comes from companies that specialize in this crap

- Red Flag #3: The brand is not sold in Japan

- Red Flag #4: It’s a blended whisky

- Red Flag #5: The age statement on the bottle is longer than the distillery has been licensed

- Red Flag #6: The abv is around 40%

- Red Flag #7: It’s oddly affordable

At the time, we discussed how a) the standards are not law, thus don’t apply to non-JSLMA members, and b) even for JSLMA members, several loopholes–not disclosed to the general public–leave quite a lot of room for exploitation. I suggested that to really drive the new standard home, the JSLMA needed to raise consumer awareness of it via stickers on bottles and/or via a centralized, official list of approved bottles. (I made an unofficial list, if you’re interested)

Over eighteen months later, the JSLMA appears to have done nothing. Liquor shops worldwide still carry brands purporting to be Japanese whisky. Some of these are labeled as “Japanese whisky,” some say only “Made in Japan,” and others might use kanji and/or some Japanese imagery on the label to imply they are from Japan.

There must now be hundreds of different “Japanese” whiskies. So rather than attempting to cover them all via that exhaustive infographic from several years back, I think it’s better to provide some pointers on what I consider to be red flags when looking at any bottle of supposed Japanese whisky.

Red Flag #1: It’s not clear which company and/or distillery makes it

This is an obvious but important one. If you’re reading this article, you’ve likely heard of Suntory, Nikka and Kirin. And probably even Chichibu. But what about the other distilleries that seem to be popping up so rapidly?

For smaller distilleries that are making genuine Japanese whisky, they are typically extremely clear with their labeling. They want their distillery name and brand out there. Akkeshi’s single malt Japanese whisky “Taisetsu” release clearly states that it’s a single malt Japanese whisky and that it’s “distilled, matured, and bottled in Japan.” Their “Daikan” release, however, doesn’t use this language because it uses imported grain whisky.

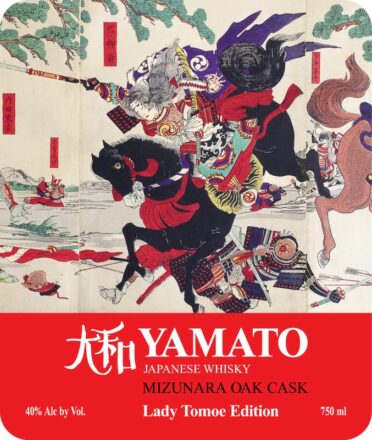

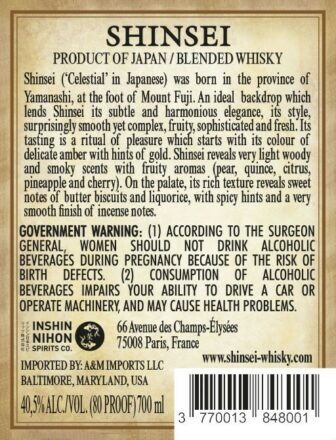

Companies that source whisky from outside of Japan and bottle it to appear as Japanese often don’t state the name of the company or distillery. They might offer some approximate location like “at the base of Mt. Fuji,” “Okinawa,” or “deep in the Minami Alps,” but won’t provide specifics.

Red Flag #2: It comes from companies that specialize in this crap

If you want to drink genuine Japanese whisky, here are some names to avoid: Minami Alps W&B, San Foods, Aiko Importers, Matsui Shuzo, and Kyoto Shuzo.

Does this mean their products are terrible? Not necessarily.

Red Flag #3: The brand is not sold in Japan

This may seem obvious, but it’s a pretty bad look if a “Japanese” whisky brand isn’t actually sold in Japan.

The internet can help you with this. Try searching for the brand name + ウイスキー in Japanese, or for example on Amazon JP or Rakuten.

Red Flag #4: It’s a blended whisky

You can count the number of industrial-scale grain whisky distilleries in Japan on one hand. (Suntory’s Chita, Kirin’s Mt. Fuji, Nikka’s Miyagikyo)

As of 2022, you can count the number of grain whisky distilleries in Japan that supply distillates to other companies on zero hands.

While there are a handful of craft distilleries with in-house grain whisky operations, they are still few and far between.

This means that if the bottle is not coming from Suntory, Nikka, or Kirin, and it’s a blended whisky, it’s almost a certainty that at least the grain component comes from outside Japan. Under the new JSLMA standard, all whisky in the bottle must be fermented, distilled, matured, and bottled in Japan. How can you tell it’s a blended whisky? Easy! Unless it’s specified as a “malt” whisky, it’s likely a blended whisky.

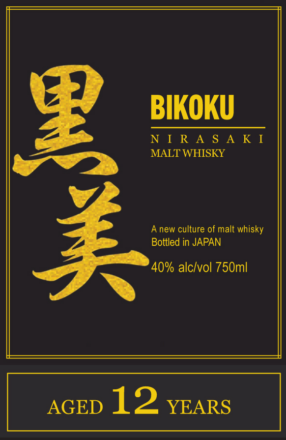

Red Flag #5: The age statement on the bottle is longer than the distillery has been licensed

This one requires some knowledge of dates of when distilleries got licensed. But if you know, for example, that the Nirasaki Distillery acquired their whisky license in only 2014, it’s (legally) impossible for them to have a single malt whisky with a 12-year age statement in 2022. You can check the Distillery Map and Distillery Tracker for this kind of information.

Red Flag #6: The abv is around 40%

In line with global tastes for premium whisky, single malts coming from craft whisky distilleries in Japan tend to be 50% abv or higher.

Companies that import malt or grain to Japan often focus on making large volumes of whisky to reduce per-unit costs. To do so, they typically add significantly more water to each bottle, reducing the strength to the bare-minimum 40% abv.

Red Flag #7: It’s oddly affordable

If a price tag looks too good to be true compared to other Japanese whiskies… it probably is.

Even here in Japan, a 3-year single malt Japanese whisky from an up-and-coming distillery can easily cost about 12000 yen or $90 USD. For foreign markets, you need to add export costs, international logistics, import duties, margins for all the middlemen involved, local marketing, and more. What is a realistic price for such a bottle in the United States or in your local market?

By using imported whisky to produce huge volumes (see #5 above), not-Japanese-whisky makers can reduce their per-unit costs, making them look downright affordable compared to bonafide Japanese whiskies.

In reality, if you’re seeking genuine Japanese whisky, you’ll need to be prepared to pay quite a lot for it.

Taken in isolation, the presence of one–or even more–of these red flags doesn’t necessarily mean a whisky is not bonafide Japanese whisky. Nor do they mean the liquid inside tastes bad! Suntory, for example, makes relatively affordable blended whiskies that comply with the JSLMA standard. Likewise, Nikka’s From the Barrel remains one of its most celebrated blends despite not being entirely Japanese.

Taste may be a matter of personal preference, and not everyone can afford genuine Japanese whisky given its high cost. One thing all whisky drinkers seem unanimous on, though, is the push for greater transparency. Nobody says, “I want to know less about my whisky.” And since none of us want to do research online while in a liquor shop, there’s no better place for that transparency than bottle labels.

Hi there! I created and run nomunication.jp. I’ve lived in Tokyo since 2008, and I am a certified Shochu Kikisake-shi/Shochu Sommelier (焼酎唎酒師), Cocktail Professor (カクテル検定1級), and I hold Whisky Kentei Levels 3 and JW (ウイスキー検定3級・JW級). I also sit on the Executive Committees for the Tokyo Whisky & Spirits Competition and Japanese Whisky Day. Click here for more details about me and this site. Kampai!

Great post!!

Thank you!

This does only apply to Malt whiskies. Any other whiskies, such as Koji style, would not, and could not follow several of these rules by simple fact of their being made with a different grain. Koji style whiskies are just as good, if not better, than their ridiculously more expensive malted counterparts, and according to the agreement with the UK, cannot be sold in Japan.

Per Japanese law, anything that uses koji cannot be a whisky. EU law agrees; it requires whisky be “fermented by the action of yeast.” US law however disagrees, saying if it’s made from grain and tastes like a whiskey, it’s a whiskey.

What UK agreement are you referring to? Thatcher did contribute to the abolition of the grading system for whisky in Japan, but koji-based drinks (sake, shochu) and “Western” drinks have been separate tax categories since 1896.

Koji whiskies can be sold in Japan. They just can’t call them “whisky.” Instead, they need to be categorized as a liqueur. That’s what Shinozaki does with their Asakura liqueur.

In terms of flavor, absolutely, some koji whiskies are great. My favorite so far is probably Tarusky or Okukuma. Both sold in Japan.

https://www.nomunication.jp/2018/05/24/review-tarusky-premium-blend-12-year-cask-aged-shochu/

https://www.nomunication.jp/2021/06/03/review-okukuma-a-sherry-cask-aged-rice-shochu/

What I have noticed something similar to #3 also happens with other spirits. There are gin and vodka branded as Japanese, but you cannot find the products in Japan, or who made them. Now, of course in this case the content might very well be distilled there and probably even taste good… but if it’s just a brand created for western markets by a western company so that they can charge extra, is it really Japanese? I suppose technically yes, but when it’s clearly just a blatant attempt to have higher margins, it leaves a bit sour taste to my mouth.

As an example, recently I’ve seen UKIYO* gin and vodka brand on the local liquor shops . They have a fancy bottles and marketing websites for their gin and vodka, but nowhere is to be found where it was actually made in Japan, or by who. Just some made up vague brand story, that this comes from this part of Japan — blah blah shochu blah blah — japanese botanicals blah blah.

*it seems like there is also whisky with this brand. What are the odds it meets the new Japanese whisky standard? 🙂

It’s definitely happening with other categories as well. With gin it’s even harder to tell because we don’t have red flags #4-6. Gin distilleries can be tiny and cost almost nothing compared to whisky. As long as they meet the minimum requirements for output, they can get licensed in Japan.

Thanks for this, I love whiskey and this was completely helpful. I was looking to buy a bottle of Japanese whiskey as a gift for a friend, with this information I can research it with more information on hand.

Glad to be of service!