Text: Mamoru Tsuchiya

Images: Mamoru Tsuchiya, Hiroshi Shibuya

Translation: Whiskey Richard

This column originally appeared in Japanese in Whisky Galore Vol.29 / December 2021.

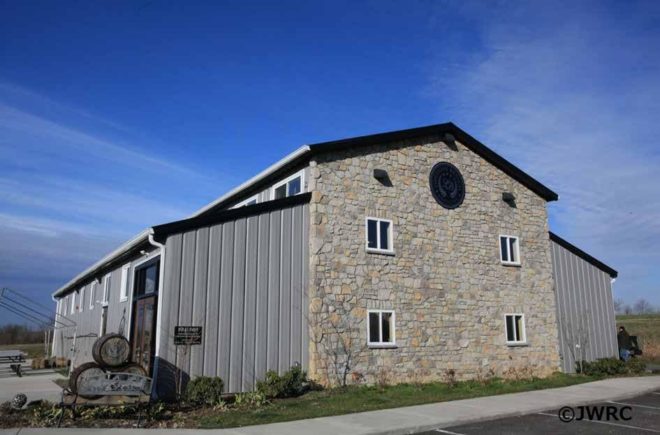

Header image: Venture Whisky’s Chichibu Distillery began production in 2008.

The unabated rise in the popularity of craft whisky and craft distilleries continues. In January 2021, we published the last volume of the Whisky Connoisseur textbook, and the distillery list totaled 35 distilleries. That number includes majors like Suntory, Nikka, and Kirin, meaning there are 29 craft, a.k.a. small-scale, distilleries. Of those, 27 were built in 2010 or later. That list included ones that were still in the planning stages, meaning they hadn’t been completed yet. In just half a year, we now need to add another five or six distilleries to that list.

The Japan Whisky Research Centre has launched a new information portal called the “Japanese Whisky Information Center (JWIC),” where we provide details about distilleries. As of October 2021, there are 32 listed on the site, and adding those in the planning stages, there are about 50.

Ten years ago I was half-joking when I said that “it would be interesting if there were a distillery in each of Japan’s 47 prefectures,” but reality has exceeded our expectations and imagination. It’s not an overstatement to say that Japan is in the midst of an unprecedented whisky boom, and a craft distillery movement.

A miraculous recovery from 25 years of lows

This is reflected in the numbers too. Japanese whisky rose alongside the post-war economic growth. In 1980, 12.4 million cases (12 bottles per case) of Suntory Old were sold, setting a world record for sales of a single brand of whisky. The taxed volume of whisky, essentially domestic consumption of whisky, peaked at 380 million liters in 1983. These are statistics from the National Tax Agency, which at the time categorized whisky and brandy as the same, so brandy is included in those figures. But whisky accounts for 90% of the shipped volume.

With 1983 as its peak, the decline began. By 1989, when the liquor tax law was revised to eliminate the grading system, consumption had already declined to 230 million liters. With the bursting of the bubble economy, things simply went downhill from there. The first year of the 21st century, 2001, saw consumption of 110 million liters, and by 2008 it was down to 75 million liters, or one-fifth of the peak. A fall from heaven to hell, so to speak.

For the 25 years from 1983 to 2008, whisky was trending downwards. It was during those years that the economic bubble burst, there was the financial crisis, growth in nihonshu and wine, and there was even a boom in honkaku shochu. While whisky was alongside for the whole ride of post-war economic growth, it’s as though when consumer tastes diversified, the category was unable to keep up.

After hitting rock bottom in 2008, whisky began to recover. In 2013 consumption hit 100 million liters, and in 2018, it was back at 170 million liters, roughly half of the peak. This brings us to the record-breaking Japanese whisky boom.

The recovery is striking not just in terms of domestic consumption, but also export statistics. Per numbers published by the National Tax Agency every year, compared to an export value of 1.7 billion yen ten years ago, 2020 saw exports worth 27.1 billion yen, or sixteen times the amount. 2020 is the first year that whisky overtook sake to become Japan’s leading alcohol export. Shochu, another distilled beverage, saw just 1/20th that much in exports. Considering the entire world was dealing with COVID-19, 27.1 billion yen is an amazing number, but things haven’t stopped there. This year (2021), from January to August, exports have hit 34 billion yen, so if the trend continues they may top 50 billion yen (ed — the final number was 46 billion yen). This is undeniable proof that Japanese whisky is continuing to grow in popularity overseas.

So, what is behind this popularity of Japanese whisky, and why did the craft boom occur? Why have there been so many new distilleries in the past four to five years?

When did the word “craft” catch on?

The history of Japanese craft whisky begins with Venture Whisky’s Chichibu Distillery. Ichiro Akuto launched the company in 2004, and in 2007 he purchased land in Chichibu, Saitama’s Midorigaoka Industrial Park, and established the Chichibu Distillery. The distillation license came through and production began in February 2008. This is when Japanese whisky was at its rock-bottom. But whisky consumption began to increase, and before anyone knew it, it experienced explosive growth.

“Craft whisky” and “craft distillery” didn’t catch on as words until after 2013, meaning that when Chichibu was established, nobody called it that. Though not Japanese, when the Kilchoman Distillery was established in 2005 on Islay, it was called a “micro” distillery rather than a craft distillery. Micro simply because it’s small. So when did the word craft catch on? For the answer, we need to look to Scotch.

Scotch peaked out in the late 1970s, and like Japanese whisky, it experienced an extreme downturn. During this period there were plenty of mergers, closures, and acquisitions, but with the turn of the millennium as its low point, whisky shipments began to recover before those of Japanese whisky. The industry was still dominated by large-scale players though, and nobody thought there was any chance for new micro-distilleries except for Kilchoman.

The biggest hurdle for new entrants was the unspoken rule that no stills under 2000 liters (technically 400 gallons, or about 1800 liters) would be authorized. 2000 liters seems like an appropriate size now, but for a craft distillery that wanted to be small, it was a matter of life and death. Then, in 2010, the Scottish Craft Distillers Association was created, and they began lobbying to get rid of the 2000 liter requirement. In 2012 the tax office finally did away with the 200-year-old unspoken rule, and by 2013 craft distilleries started popping up in Scotland. As of this writing, there are about 60.

The same thing is occurring next-door in Ireland. Until 2014, Ireland had only four distilleries: Bushmills in the north, the New Midleton Distillery in the south, then there was Cooley and Kilbeggan. There are now almost 40. That craft wave came to Japan around 2015/16, and the first out of the gate were Akkeshi, Mars Tsunuki, Asaka, and Gaiaflow Shizuoka. This is some six to seven years later than Chichibu. And what happens to Japanese craft whisky next needs no explanation.

Single malts support the craft movement

There’s another special aspect of the worldwide craft shift. It’s that many are aiming to create single malt whiskies. America was the first to see the growth of craft, and these days it’s said there are around 2000 distilleries you could call “craft” in America. At the beginning many made Bourbon, corn, and rye whisky. But the focus is now on craft distilleries making single malt whiskies.

American whiskey does have a definition of malt whisky, but no specific definition of “single malt.” And unlike Scotch, Irish, or Japanese whiskies, American whiskies can be called malt whiskies if they use 51% or more malt (malted barley). This is a far cry from the 100% malt requirement of other countries’ malt whiskies. As a result, distilleries trying to make 100% malt whiskies in America have a disadvantage. There are efforts being made to try and create a definition of “single malt” in America for this reason.

In any case, what’s driving the craft boom in other countries is single malt whiskies. Single malt whiskies offer a wide variety of profiles compared to blended whiskies. Were it not for the growth of single malts in the late 90s to the new millennium, there likely wouldn’t be any craft movement or many craft distilleries today. The market would continue to be entirely occupied by blended whiskies, and craft would never have occurred. The blended whisky industry requires enormous capital to enter, making it impossible for smaller competitors to emerge.

Key points: environmental protection, tourism, and local economies

By necessity, the world arrived at single malts by seeking out diversity in whisky rather than uniformity. Without single malts, we would not have this worldwide whisky movement, and certainly not any craft growth. The pace at which the world consumes information has accelerated drastically versus 20 years ago, and with that have come changes to peoples’ lifestyles and more diversity in their preferences. From anywhere in the world, you can access information about distilleries instantly, and even purchase bottles. No matter how far away from civilization or remote you build a distillery, there are essentially no demerits, and anyone can buy bottles via the internet. This means that, with the craft movement, our information society no longer requires distilleries be located close to where the products are consumed.

In conjunction, revolutions in whisky distillation technology, SDGs focusing on the Earth’s environment, and sustainability practices are keywords for the craft whisky scene. The current craft whisky boom has also been recognized for its potential to help revitalize local economies, and inspire distillery tourism. Sake tourism and wine tourism already exist, but both sake and wine are produced seasonally, meaning not year-round.

And that’s not to mention that the fermentation process is hard to see from the outside. Fermentation anywhere essentially looks the same. Whisky, on the other hand, is produced year-round, meaning anyone can see production first-hand, and no two distilleries are the same. Distilleries also support local economies through local hiring and purchasing raw materials from local producers. The craft distillery movement and popularity of craft whisky are closely related with such trends not just in Japan, but at a global level.

Mamoru Tsuchiya is Japan’s foremost whisky critic. He is the Representative Director of the Japan Whisky Research Centre, and was named one of the “World’s Best Five Whisky Writers” by Highland Distillers in 1998. He served as the whisky historian for NHK’s Massan and he has published several books such as The Complete Guide to Single Malt Whisky, Taketsuru’s Life and Whisky, and The Literacy of Whisky. He is the editor of the bimonthly Whisky Galore, Japan’s only print whisky magazine.

One Comment