The Kampai Samurai interview series brings together experts in Japanese whisky, sake, shochu, beer, gin, and other categories to explore the breadth and depth of Japan’s drinking culture.

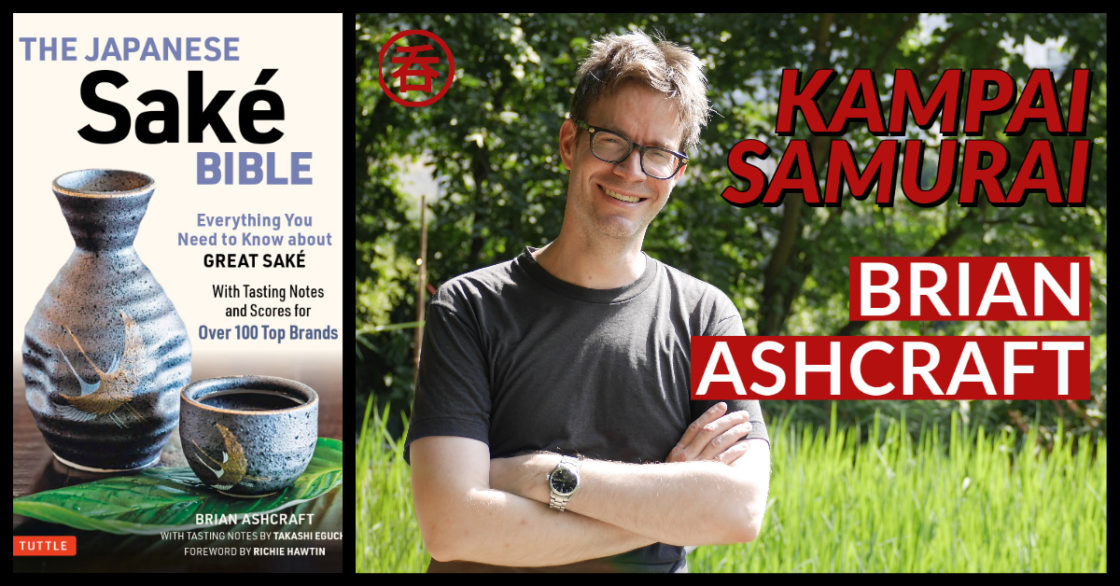

Many of you probably know Brian Ashcraft for his work at Kotaku, where he is a senior writer. He has lived in Japan since 2001, and he has written six books about Japanese culture since then.While I’m confident I can destroy you in Bushido Blade, we’re here to talk about drinking. Brian’s latest book, The Japanese Sake Bible: Everything You Need to Know About Great Sake – With Tasting Notes and Scores for 100 Top Brands (Amazon JP/US) is slated for release on September 15, 2020.

His writing about alcohol goes back to 2005, when his piece for Wired about absinthe invigorated discussions about the spirit’s legality in the US. Many of you probably also read his 2018 book Japanese Whisky: The Ultimate Guide to the World’s Most Desirable Spirit with Tasting Notes from Japan’s Leading Whisky Blogger.

You can follow him on Twitter. and of course over at Kotaku.

Today we speak with Brian about his new sake book, sake in general, and a bit of whisky as well.

Whiskey Richard: You’ve written a ton about many different facets of Japan, including the well-received Japanese Whisky: The Ultimate Guide to the World’s Most Desirable Spirit with Tasting Notes from Japan’s Leading Whisky Blogger just a couple years ago. Now you’ve set your sights on sake, with The Japanese Sake Bible: Everything You Need to Know About Great Sake – With Tasting Notes and Scores for 100 Top Brands set to be released next month. What can you tell us about your relationship with sake, and what can we expect in the book?

Brian Ashcraft: Growing up, my parents had sake sets in the bar in my family home. Even as a kid, seeing how different those delicate little cups were next to the beer stein collection was striking. My mom was into sake during the late 1960s and early 1970s, so whenever we would go eat Japanese food as a kid, she would inevitably bring up sake. So even though I was just a kid and obviously didn’t drink, sake was around, and I was intrigued.

When I moved to Japan in 2001, I didn’t have much money and was surviving on convenience store food. I started drinking Ozeki One Cup, and liked how you could get a pleasant drink plus a high-quality glass cup. I thought it was an amazing deal and still do. But it was in 2005 that everything changed when I visited my first brewery in Nara, and then started visiting others. I was amazed at the process and how breweries could create all these interesting complex flavors.

So I’ve long been interested in sake and am delighted to have had the chance to work for this book for the past few years. Making a book like this is time-consuming. My co-author and I visited over 150 breweries all across the country. Sake is a deep, daunting subject! A delicious one, too.

The English speaking world is very fortunate to have an excellent canon of sake books. But, I really think we need more–not just my book, but many more sake books in general. Look at all the wine, beer, and whisky books published each year–each month, even! Sake should not be a niche product. It’s too damn good. So the goal of myself and my co-author Takashi Eguchi is to contribute to the conversation about the drink and hopefully help push the ball down the field. The book is filled with interviews, info, history, and culture, and I tried to write it in a lively interesting way. If you liked my previous book Japanese Whisky or my tattoo book, you’ll probably like this. Both the whisky and sake books are, in my mind, a set.

WR: In Japanese Whisky, it’s right in the title that the tasting notes are provided by someone other than yourself. From what I’ve gathered, you’ve taken the same approach with The Japanese Sake Bible. I’ve always been a fan of getting multiple opinions about a particular bottle, so I must ask, did you consider doing a side-by-side tasting session with Eguchi-san? I think a lot of people would be interested in your opinion of the bottles that are presented.

BA: I am a big fan of collaboration. When I do a book with someone, I want to work very closely with the collaborators, and I think that’s the only way for the project to be successful. If I have a collaborator who, for example, won’t answer emails or phone calls, and with whom I cannot speak to almost every day, the collaboration just won’t work. The book emerges from those conversations with my co-authors.

Also, I believe it’s essential to give Japanese people a voice regarding these drinks. This is their drink culture and history. I’m an American–granted, I’ve lived in Japan for nearly two decades, but still their insights are extremely important, I believe. For a book on Japanese whisky and Japanese sake, I strongly believed that Japanese collaborators needed to be intimately involved. Also, I felt very strongly that they should describe their country’s drinks. This would lead to a greater understanding of Japanese flavors and the drinks themselves.

So, I set out to find collaborators I respected and would enjoy working with, and I was very fortunate to do so. While I wrote the main text and they wrote the tasting notes, we talked about what we were writing with each other, to ensure a cohesive narrative and that their insights and points of reference would be understood by a larger, non-Japanese audience and, at the same time, did not compromise the intended meaning.

I view sake in a similar light to my co-author Eguchi-san, and I view Japanese whisky in a similar light to co-author Kawasaki-san. That’s why I wanted to do a book with them and that why these collaborations worked.

WR: Sake is one of Japan’s recent export success stories, with exports tripling in value and doubling in volume over the last decade. What is it about the drink that people outside of Japan find attractive, and do you expect this kind of growth to continue?

BA: The easiest answer is that it’s a delicious drink. Sake is truly great. It comes in a variety of styles, it can be drank a bunch of different ways, and it pairs very well with food.

Right now it’s a truly great time to be a sake drinker, considering all the excellent, varied brews that are available. The pandemic is certainly impacting the industry, and yes, moving forward, I am bullish on the success of sake outside Japan.

WR: Are there any specific regions of Japan or brewers whose sakes jumps out at you? I’m partial to Niigata’s light and dry style, since I’m up there almost every winter weekend snowboarding.

BA: I love sake from all over the country, but perhaps, sake brewed in Kansai is closest to my heart, due to its historical and cultural importance and also because it’s so darn good. Kyoto, Hyogo, Osaka, Shiga are home to some of the best, and most interesting breweries in the country. Places like Akishika, Uehara Shuzo, Kinoshita Shuzo, Honda Shoten, and Emishiki are all doing very interesting things as are the region’s, and the country’s, biggest breweries like Kenbishi and Kiku Masamune. The wealth and variety of sake in Kansai, and in turn, the entire country is one of the most appealing things about sake.

WR: Speaking of regions, what’s your take on terroir in sake? Does it exist?

BA: Previously you mentioned Niigata, and I think that’s a good prefecture to discuss regionalism or, as you mentioned, terroir. Niigata actually has a much more varied style of sake than it’s typically given credit for. The karakuchi tanrei (dry and crisp) style certainly has become emblematic of Niigata sake, but the prefecture didn’t always make that. In the decades after World War II, when the heavier Nada style was popular, Niigata breweries were also brewing in that style during the 1960s. So while a prefecture or an area might be known for a certain style now, these styles do change. Remember, sake is the result of a series of decisions made by the brewers. Even today, some Niigata brewers are moving away from karakuchi tanrei to a more tanrei style. So we can talk about hallmarks of a regional style or what a region is known for, but we need to understand that those style can and has changed.

Other breweries do not even brew for local customers but rather, have their eye on larger markets in Tokyo and Osaka, and are making styles of sake that perhaps appeal to current trends and flavors.

Now, certain types of water and certain types of rice do lend themselves to certain brewing styles. But many breweries bring in rice from other prefectures, and even truck in water. What does this mean for regionalism? There might be an idea that for a brewery to be truly local, it needs to just rice from a nearby field with the local water. But then, what about the yeast? What if the brewery is buying yeast from the brewing association? Is that still local? Should a brewery only use ambient yeast? What if the brewers themselves are coming in from other towns or prefectures? Is the sake still local? Defining locality and terroir are very difficult. Compared to Japanese whisky, which save for some exceptions, is made from imported barley and then aged in imported casks, sake is an incredibly regional product–but by that, I mean, the entire nation of Japan.

WR: What are some other trends going in the sake world right now?

BA: I feel like hot sake is getting a second look after a big push to drink chilled brews. Philip Harper at Kinoshita Shuzo has been championing the style–which makes sense because his sake is great hot, even his summer namazake, but also because the different serving styles really underscore the seasonal nature of sake. So, during summer, I want to drink fresh, lively, tart, cold sake. But during the fall and winter, I want to drink savory hot sake. Yet, at many, but certainly not all, sake bars in the country, even when the weather gets cooler, chilled sake often seems to be the default. Japanese food is seasonal, and so is sake.

In the past few years, there has been a rush to procure wood tubs to brew because a legendary cooper was retiring, so there has been an interest in this older method of brewing, instead of using enamel tanks.

Also, I’m seeing interest, especially from non-Japanese friends of mine, in long-aged sake, which has many flavors that might be familiar to whisky drinkers.

As I mentioned above, flavor-wise, it’s really an interesting time for sake.

WR: In Japanese whisky we’re seeing craft makers increasingly lean towards “Japanese” approaches, Shizuoka Distillery for example using cedar washbacks (ala sake), Akashi with their ex-sake casks, and more reliance on local barley. But other companies are simply taking rice shochu and labeling it as whisky outside of Japan. What are your thoughts on this practice, and where do you see things going in the intersection of Japanese whisky with sake/shochu?

BA: I’m not a fan of shochu being rebranded as “Japanese rice whisky.” That’s nonsense. Shochu is shochu, and it’s great, and I think any company that’s trying to rebrand it is simply trying to pull a fast one. If you are making shochu, you have any reason to be proud of that, so brand it as such.

Japanese whisky has a very specific history that is tied to both Scotland and the United States. Scotland, obviously, has had the biggest impact on the way that whisky is made in Japan. (Though, at a place like the Kirin Distillery, we can see the influence of American and Canadian methods.) So, for me, Japanese whisky needs to be made with traditional whisky grains. If koji-kin is involved, then it’s not Japanese whisky. At that point, it moves into the shochu category.

However, for aging and other production methods, Japan has long shown great creativity and flexibility, and that is unique.

Today, most sake is not brewed in wood, nor is stilled or finished in wood. When you see breweries that use wood, there are typically two approaches: either very noticeable wood aromas or very subtle (or hardly any) notes. The kioke wooden tubs are traditionally coated or sealed in kakishibu or persimmon juice so that the wood last longer. There are microorganisms that live in the tubs, such as between the staves, that then impact flavor, so you might not end up with a very woody sake, but instead, one with more depth. (But it certainly is possible to pick up astringent or wood nuances!) The other thing you see at breweries that maybe only have one or two of these tubs is that they are making a special release and appeals to the way the sake is brewed. So, they might not use kakishibu and even have the inside of the tub shaved, so make the brew noticeably woody.

This is also what you see with taruzake–or cask sake. The brewed sake is finished in a small cask that has had the inside shaved, so the result is noticeable sharp cedar flavors.

As for what Eigashima Shuzo is doing, they’re filling a cask with sake, I believe, and then using that cask to age whisky. It’s an interesting idea. Of course, I’ve also had sake that’s been aged in casks. This is all interesting, I think, and I’ve enjoyed the releases I’ve had.

The sake and whisky worlds are very different in Japan. Eigashima Shuzo is unique in that regard. But even when you go to a whisky bar, it’s whisky. When you to a sake bar, it’s sake. Now, if you go to a fancy restaurant, both exist on the menu. I would rather drink sake with a meal and whisky after it–unless I’m eating something like takoyaki, because then bring on the highballs. So, in Japan, these drinks serve different functions.

What really blows my mind is seeing people in the supermarket fill their carts with mass-produced chu-hai, which is really fizzy water, alcohol, and flavoring–when they could get a bottle or two of excellent, sake made with Japanese rice and made with great care and time. (Obviously, it’s great to see people picking up bottles of shochu, though!) Making sake is so difficult and so taxing, and I feel like that even in Japan, it can be taken for granted.

For me, I really want sake to be normalized like whisky is. We have Scotch whisky, Irish whiskey, American whiskey, Japanese whisky–all these different types of whiskies around the world. I hope that the same thing happens with sake. I’ve had excellent Vietnamese sake, great Mexican sake, and terrific American sake. I hope these segments grow more and more and become much more established, and more importantly, entrenched in drinking cultures around the world to the point that people don’t default to Japanese food for sake.

WR: Since you’re a long time resident of Japan, let’s talk about COVID-19 and its impact on the drinking scene here. One of the things that a lot of tourists seek out when they come to Japan are the hole-in-the-wall yokocho-style places not much larger than a closet. How do you think things are changing for those of us that live here, and how will things change for visitors in the future?

BA: As you well know, the restaurant and bar industry is being hit hard. The government is trying to support small businesses, but the losses are still huge. This has a knock-on effect to production, and then to agriculture. I really hope this pandemic can be eradicated as soon as possible because not only of the health risks but also to how it is impacting society at large.

I miss going to bars. I miss going to events. I miss going to breweries and distilleries. This year has been bad on multiple fronts. I have been trying to support breweries and distilleries who make my favorite stuff, and I hope fans of Japanese sake and whisky within the country and abroad are doing the same. How will things be after covid? I honestly do not know. But these industries have proven themselves to be incredibly resilient over the course of Japanese history. I hope they will continue to be so.

Hi there! I created and run nomunication.jp. I’ve lived in Tokyo since 2008, and I am a certified Shochu Kikisake-shi/Shochu Sommelier (焼酎唎酒師), Cocktail Professor (カクテル検定1級), and I hold Whisky Kentei Levels 3 and JW (ウイスキー検定3級・JW級). I also sit on the Executive Committees for the Tokyo Whisky & Spirits Competition and Japanese Whisky Day. Click here for more details about me and this site. Kampai!