You wouldn’t know it from the hype around exports, but sake is actually in a bad way at home. Production peaked in the early 1970s and has been on the decline ever since. Total volume produced has dropped to one third of what it was, and sake accounts for only around 7% of the domestic drinks market.

There are some interesting recent trends, including exports setting new records year on year. And domestic consumption of futsushu or table sake falling, while most of the “premium” classifications gain ground, with the result that the downward trend is easing slightly.

What happened? Probably a combination of things: ready availability of “exotic” foreign drinks like wine and beer, changes to Japanese eating and drinking habits, an overall decline in alcohol consumption among young people, and changes to company culture that have seen alcohol-fueled group evenings out become a thing of the past. Many breweries complain that sake is seen by young people as something their grandfather drinks, leading to diversification into low-alcohol, sparkling and fruity variants.

Brewery response

Sake expert John Gauntner estimates that many breweries are operating at minimal profit, or even running at a loss if they’re one company in a portfolio of businesses owned by the same family. Brewers struggle not only against rising production and transport costs but also consumer ideas about how much sake should cost. Some fight back with presentation, regularly changing their product lineup and raising prices, or adding extra touches such as boxes. Others have abandoned the classification system entirely as they see it as the source of price preconceptions. And some are trying to go high-end, modelling themselves on French wine, and charging prices never seen before.

Sake expert John Gauntner estimates that many breweries are operating at minimal profit, or even running at a loss if they’re one company in a portfolio of businesses owned by the same family. Brewers struggle not only against rising production and transport costs but also consumer ideas about how much sake should cost. Some fight back with presentation, regularly changing their product lineup and raising prices, or adding extra touches such as boxes. Others have abandoned the classification system entirely as they see it as the source of price preconceptions. And some are trying to go high-end, modelling themselves on French wine, and charging prices never seen before.

The sake industry is also a very uneven one. The government estimates there are around 1,200 licences issued to sake breweries, although not all holders are actively brewing. The ten largest companies – less than 1% of the total – are responsible for almost half of all sake production. The top three alone (Hakutsuru, Takara/Shochikubai, Gekkeikan) produce almost one third. These big companies have the commercial clout to get into Japanese restaurants and Asian food shops overseas and supply the bulk of anonymous sake served hot or cold in restaurant chains.

Drinking like a local

In Japan, the situation is different. High quality jizake – almost literally “local” sake – can be found everywhere, even in a convenience store close to the brewery. The heavy concentration of mass production in the top few companies means that learning and avoiding between three and ten names will guarantee you get sake only from small or medium sized breweries. That’s not to say that what the big breweries produce is bad, it’s anything from average to good enough to win at international competitions. But for those interested in craft production and innovative and/or traditional brewing, small is beautiful.

I’m a huge fan of jizake. Not only is it small-scale and more or less hand-made, if that’s what you’re into, but the people are amazing, hard-working, passionate, and incredibly generous and welcoming. I got into sake through translation, but there’s no question I’ve stayed for the brewers, promoters and importers that it’s been my great pleasure to meet.

Finding your favourite sake

That said, I don’t tell people which sake is best. To paraphrase a friend who works in coffee, the best sake is the sake you like. Try as many as you can, use the information on classifications and styles to explore the diversity that it has to offer, and find the regions, breweries and labels that speak to you.

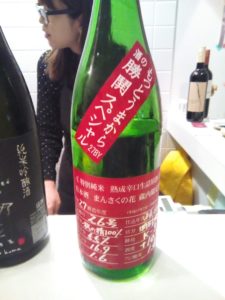

However, I do have two recommendations to get the best out of your sake. First, buy from a specialist retailer or drink at a specialist bar. They’ll have a better range, can give you advice and will also store their inventory properly. Sake isn’t particularly delicate, but it is vulnerable to heat, especially if it’s not pasteurised, and also light. Beware of any bottles (especially clear glass) stored in full daylight or bright fluorescent light, and back away slowly from any sake that is noticeably coloured unless it’s due to no charcoal fining (muroka) or ageing (jukuseishu, koshu), or has anything floating in it unless it’s coarse filtered (nigori).

Sake in the home

Second, take a little care with storage at home. Keep sake out of the kitchen (where it can be at risk from heat) and store it in a cool, dark place. Refrigerated is ideal, but not necessary unless it’s not pasteurised. Open bottles can be vacuum sealed with a wine saver system and put in the fridge, where they’ll keep around 7-10 days. After that they will start to lose aroma and flavour, although they’re still safe to drink and can be used for cooking or in cocktails.

If you don’t think you’ll make it through a full 720 ml bottle, look out for 300 ml “half” bottles or 180 ml “one cup” containers – they’ll range from mass-produced standards from the big breweries through fun 200 ml “super-size” cans from medium sized companies to beautifully decorated chances to sample smaller ones.

If you have sake cups or glasses, great – vessels with thick rims are particularly good for sake on the umami end of the spectrum. But don’t feel you have to invest in some to get started. All you actually need to enjoy sake are two things you probably already have – a wine glass and a fridge.

Experimentation

Experiment with temperature. Try delicate daiginjo chilled and keep trying it as it comes up to room temperature. Let ginjo warm up a little more until it’s cool. Start honjozo or non-daiginjo/ginjo junmai at room temperature, or boil a pan of water and stand the bottle in it for a few minutes to bring it up to around 50°C (122°F) and taste it as it cools down. There are no hard and fast rules. More delicate and floral sake generally does best chilled or cool, but I’ve been served a hot daiginjo by the brewer (and it was divine). Have fun seeing how each sake responds to heating or cooling and find its sweet spot.

The same goes for food pairing – use a few guidelines to orient yourself, then explore. Start off by matching by intensity, delicate sake with delicate food and more intense (sweet or umami) sake with more powerful flavours. Cheese or dried meat are great pairings, but experiment. Curry. Creamy pasta sauce. Things that don’t pair well with wine. Take full advantage of sake’s versatility.

I hope this series of articles has made you thirsty to find out more! If you have any questions please leave them below, and I look forward to seeing you again on nomunication.jp soon.

Based in Zurich, Switzerland, Arline is a professional Japanese to English translator and founder of taste-translation.com. She holds a trio of sake certifications: Wine and Spirits Educational Trust (WSET) Level 3 Award in Sake, Sake Service Institute International Kikizake-shi, and Sake Educational Council Certified Sake Professional.