Today I’ll walk you through something that sets Japanese beer apart from beer in the rest of the world.

Whether you’ve just knocked off work or you’re looking for your second wind, a nice refreshing beer will probably help you on your way. If you’re American, your first question might be: so what do they have on draft? Well unless you’re at a beer bar, the answer in Japan is usually just beer. Izakaya and bars generally don’t have room for multiple taps. So they’ll have only one kind of Japanese beer available. And yup, it’s a lager.

It’s not all bad news though. I’m going to let you in on a little secret:

For domestic Japanese beer, draft, bottles, and cans are all the same freshness

As an American, that came as a bit of a shock to me. If you want fresh beer in America, you get something that comes out of a keg. Not a bottle or a can. Right? But in Japan, that’s not always the case. Let’s go into a bit more detail.

To order a draft beer in Japan, you ask for 生ビール, nama bi-ru. Your beer will be served out of a keg, it’s cold, you’re drinking, inebriation follows, you’re happy.

But here’s the thing. Technically speaking nama bi-ru does not mean “draft beer” – it would be more accurately translated as “raw beer.” This isn’t some kind of language barrier. Japanese people themselves ask for nama bi-ru when they want draft beer (often shortened to just nama). The nama means the beer is unpasteurized. That’s it. It says nothing about how the beer is served.

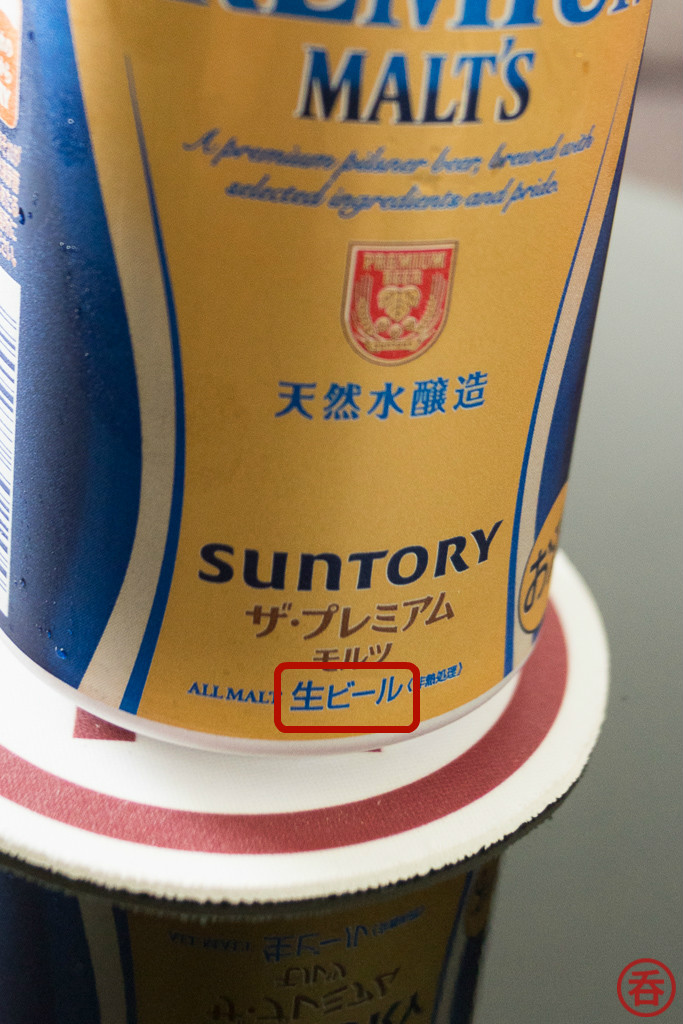

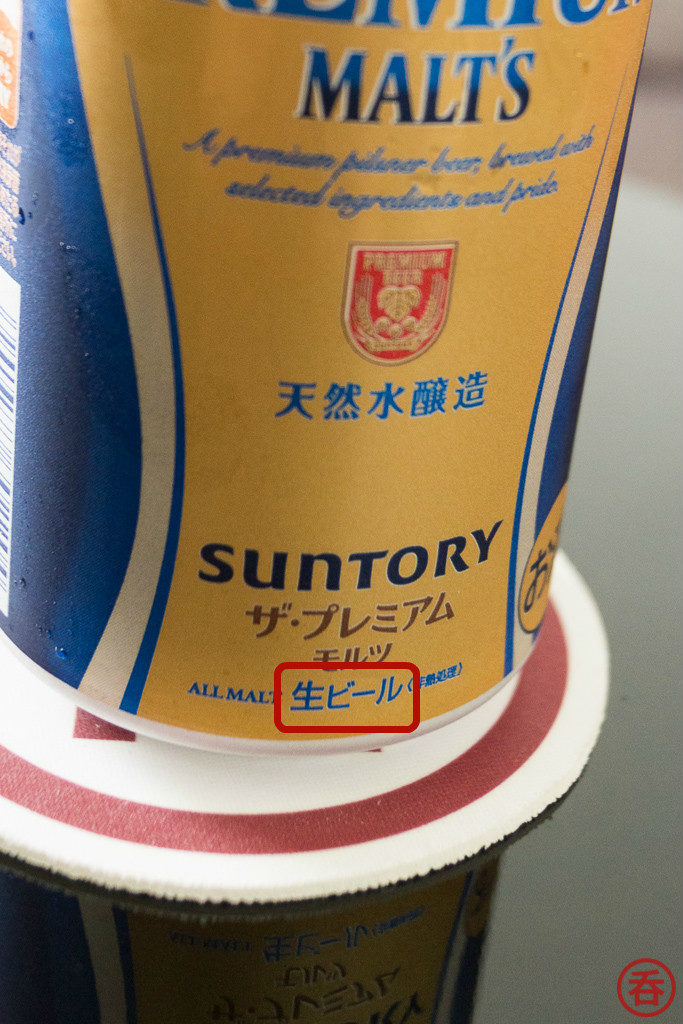

Try asking for a bottle of beer (瓶ビール, bin bi-ru) at the izakaya or bar. Or even a can of beer from the grocery store or combini. Look closely at the label. See this?

That’s right, it’s the same nama bi-ru. The same beer that beer companies put in their kegs. Cans, bottles, and kegs of beer made in Japan are unpasteurized. The freshness is all at the same level! Don’t be concerned that unpasteurized = may contain harmful bacteria. Japanese beer isn’t pasteurized, but it is microfiltered.

In this wacky world where only the container differs, draft beer and bottled beer can go head-to-head. Remember, it’s just two ways of serving the exact same product. So let’s compare!

| Draft (the misnamed 生ビール nama bi-ru) | Bottle (瓶ビール bin bi-ru) | ||

| Pros | Cons | Pros | Cons |

| Could be newly tapped | Could be not newly tapped | Consistently fresh | Have to pour for people |

| Glasses may be frozen | Draft lines may be nasty | Consistent carbonization | Glasses are smaller |

| Usually served very cold | Inconsistent carbonization | Better cost performance | Glasses rarely chilled |

| Better for sake bombs | Get to pour for people | ||

So are you going to risk it and go for the draft beer? Or do you prefer the consistency, guaranteed freshness, and cheaper price of the bottled beer?

You be the judge. My advice is try the draft beer first. If it tastes a bit off, switch to the bottle.

Just FYI, when Tom Hanks visited an izakaya during his trip to Japan last year, he chose bottled beer:

Just an aside: Pasteurization in Japan predates Louis Pasteur by centuries

Pasteurization actually has a very long history in Japan: it goes back to the Late Heian Period, the 12th century. That’s around 700 years before pasteurization was discovered by Louis Pasteur in 1864! The earliest written record of using fire to heat sake specifically for the purpose of killing off bacteria is the 御酒之日記 (go-shu no nikki) written in 1489. Japan had already been making sake for centuries at that point, so they certainly knew what they were doing. When making sake, the process is called 火入れ (hi-ire). But I’ll save the sake discussion for a different article!

Hi there! I created and run nomunication.jp. I’ve lived in Tokyo since 2008, and I am a certified Shochu Kikisake-shi/Shochu Sommelier (焼酎唎酒師), Cocktail Professor (カクテル検定1級), and I hold Whisky Kentei Levels 3 and JW (ウイスキー検定3級・JW級). I also sit on the Executive Committees for the Tokyo Whisky & Spirits Competition and Japanese Whisky Day. Click here for more details about me and this site. Kampai!